The Gravestone of a Ghost Town

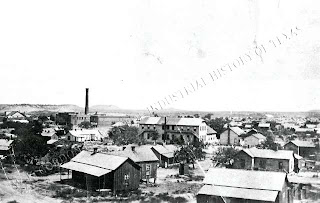

At one time, Thurber was the largest city between Fort Worth and El Paso boasting some 10,000 plus residents. The most important coal mining site in the state of Texas, it was a major manufacturer of paving bricks and the headquarters of the company that discovered the nearby Ranger oil field. Today, Thurber is home to a mere handful of families, two restaurants, a museum, and a few remaining buildings that provide insight into the town’s history. However, one prestigious and iconic structure, unlike the rest of Thurber, has survived the test of time. Anyone who has taken a trip between Abilene and Fort Worth on Interstate 20 has come across this edifice serving as a de facto monument to Thurber’s once glorious past. The 148 foot smokestack is visible from miles away in every direction.

The origins of the smokestack can be traced back to a series of renovations to the existing ice plant. From 1889 to 1890, the ice that was used in Thurber was provided by saloon keeper Thomas Lawson. After June of 1890, the Texas & Pacific Coal Company provided ice for the town. When the company took over the saloon and overall demand increased, Colonel Robert D. Hunter, president and general manager, decided to build a seventeen ton ice plant. The total cost for this operation was detailed in the company’s 1896 annual report. “It has been necessary to expend $16,169.82 in additions to buildings and new buildings, and I have erected and put into operation an ice plant and cold storage, at a cost of $20,619.01…” The new ice plant produced all the ice used by the residents of Thurber, the cold storage, the markets, and the saloons. Any of the remaining ice was sold as surplus to surrounding communities and to the Texas and Pacific Railroad.

After twelve years, the plant required an expansion which resulted in the creation of Thurber’s most famous landmark. The extent of the renovations are listed in the Texas and Pacific Coal Company’s Annual Report for 1908.

Owing to the increased demand for the product of the plant together with the greater need for better refrigeration facilities it was deemed advisable to overhaul and make certain improvements in the Ice Plant. These improvements consist of the purchase and installation of New Boilers, Automatic Stokers, New Brick Stack, new Feed Water Heater and Purifier and the construction of a Boiler House, for which expenditures were made during the year amounting to $26,775.58.

Like many new feats of engineering, the smokestack went through a christening process. However, this procedure was not performed in the traditional fashion. In her book, The Birth of a Texas Ghost Town: Thurber 1886-1933, author Mary Jane Gentry recounts this event. “The daughter of one of the men who helped build the stack often tells the story of how her father climbed to the top of the smokestack, swung one leg over the rim, gulped down the whiskey in his flask, christened the stack by smashing the empty flask on its side, and then hurried down the ladder before the ‘altitude’ could make him dizzy.”

Unfortunately, Texas’s most important coal producing site met its demise in the 1930s. All but a few buildings were sold and carted away. Houses and entire commercial buildings were dismantled or moved, water and gas pipelines were sold for salvage, railroad tracks and equipment removed, and the inventory of mining gear liquidated. Though the other smokestacks at Thurber were razed, the one associated with the ice plant was did not suffer the same fate. Through the intervention of former company general manager W.K. Gordon, the smokestack was left untouched to commemorate the town’s former glory. After 102 years the smokestack remains as one of the last tangible connections to Thurber’s past.